Bitcoin is an account, not a token

When economists talk about payments, they often make a distinction between token-based and account-based payment systems. In a recent post at the New York Fed's Liberty Street blog, Rodney Garratt & cowriters argue that new payments technologies like bitcoin and central bank digital currency may not fit into these traditional categories. Perhaps it's time for a reorg?

In an account-based system, some sort of database stores account information. For a payment to occur across this database the payer needs to prove that they own a spot in that database, and that this spot has sufficient funds.

With a token-based system there is no database. Instead, objects are used to pay (say banknotes or gold coins). The key feature of a token-based system is that the recipient must verify that the object is valid and not counterfeit.

In short, tokens involve identifying the object. Accounts involve identifying the individual.

Garratt et al argue that a digital currency such as bitcoin is a mix of the two, token and account. Bitcoin is an account-based system because some sort of "proof of identity," specifically a private key, is needed to transact. This puts bitcoin in the same category as a bank account, which also has a process for verifying the identity of users. (Instead of public key cryptography, bank customers must go through a due diligence process, and after that must produce a PIN.)

I think Garratt et al are right about bitcoin being an account-based system. But I don't think that bitcoin also qualifies as a token-based system.

Not a token

A token is an object. And objects can be counterfeited. That's why when Alice pays Bob a $20 note, Bob is responsible for carefully checking it.

Account-based systems don't suffer from counterfeiting problems. It's impossible for a Alice to pay Bob with fake dollars from her Wells Fargo account. Wells Fargo dollars aren't independent objects in the same way that banknotes are. They are entries in a well-secured database. The same goes for bitcoins. There is no way for Alice to make a fake bitcoin entry and send it to Bob.

In addition to counterfeitability, I'd argue that another key feature of a token is that it can be lost by one person, found by another, and then reused for payment. If Bob loses either his $20 banknote or his gold Krugerrand, Alice can find them and spend them.

But account-based systems don't have this feature. Wells Fargo dollars are database entries. It'd be impossible for Alice to lose a Wells Fargo database entry or Bob to find one and reuse it. And the same goes for bitcoins. Alice can't lose 0.2234 bitcoins, nor can Bob find Alice's 0.2234 bitcoins.

Gift cards: account or token?

What about gift cards, say like those iTunes cards that they sell at pharmacies?

Because gift cards come in physical form they may seem like tokens. But the card is just one element in an account-based system. A $20 iTunes balance exists in a database run by the gift card system operator, Apple. Whereas a $20 banknote can be used without the authorization of the central bank, an iTunes card has to be granted permission before it can initiate purchase. If the database entry to which an iTunes card is linked is empty, then a payment will be denied.

Like other account-based systems, counterfeiting isn't a problem with gift cards. Database entries can't be produced with an inkjet printer. (Sure, an iTunes card can be lost and reused by the finder. And so it seems like it should be classified as a token. But that's only because the "key word" or "password" is literally baked onto the card. Losing an iTunes card is like losing one's private bitcoin key.)

Bitcoins and gift cards can be turned into tokens

There is an interesting situation in which gift cards or bitcoins can be converted from account-based systems into token-based systems.

Instead of using her $20 banknote to pay Bob, Alice may choose to pay Bob by passing him a $20 iTunes card. Or maybe she gives him a physical Opendime hardware wallet that holds $20 in bitcoin. Bob could in turn pass these devices on to Charlie, to whom he owes $20, and Charlie on to Dave, etc.

In both cases, accounts are being repurposed as tokens. What is happening is the physical object, or key, that provides access to underlying bitcoin or gift card database entries is being moved from one person to another. But the actual database entries to which the Opendime and iTunes card are linked are not being updated.

Bob will have to treat both of these proffered instruments like cash. He'd be worried about counterfeits, and would want to verify that neither the gift card nor the Opendime device are fake.

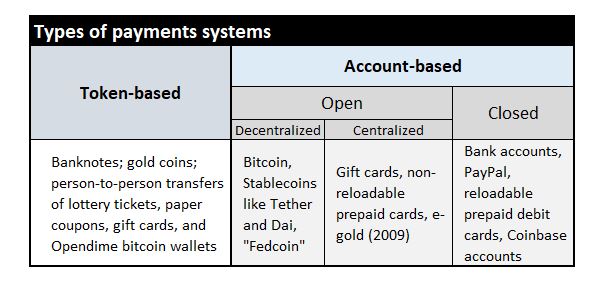

Let's vizualize all of this into a table:

The table suggests that bitcoin exists in a totally different category than a banknote (unless those bitcoins are embodied in the form of an Opendime device). You'll also notice that the table differentiates between open accounts and closed ones. Let's get into that next...

Bitcoin and Wells Fargo are different types of accounts-based systems

If bitcoin qualifies as an account-based system, it is certainly different from Wells Fargo's system. I'd argue that Wells Fargo operates a "closed account" system while Bitcoin functions as an "open account" system. The key feature of an open system is that anyone can get an account. As Jerry Brito would put it, they are permissionless. A passport or driver's license isn't required to gain access, so even fraudsters can climb aboard.

Gift cards, non-reloadable prepaid cards (like Vanilla cards), and e-gold (a 1990-2000s era payments system that didn't require people to use real names) are also open account systems. Anyone can self-initiate account opening and start to make payments. No one gets kicked off. (We could further differentiate between centralized and decentralized open account systems, with gift cards being the former and bitcoin the latter.)

What qualifies something as a closed account system is that not just anyone can get access. Want to use a Wells Fargo account for making payments? You'll have to make it through Wells Fargo's application process, which involves giving up plenty of personal information. And only when a Wells Fargo employee has opened an account can payments be made.

Turning bitcoins, gold, and cash into closed account systems

Incidentally, it's also possible to convert tokens and open accounts into closed accounts. The London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) manages a walled garden of gold bars. Each bar is carefully vetted prior to entry into the system, and once in the system all movements are tracked by monitoring serial numbers. LMBA gold has ceased to be a token and has become a closed account. (I recently wrote about the LBMA system for Coindesk.)

Central bans could do the same with cash. They could set up an online bank note registry, and all cash users would be required to sign-up and record the serial numbers of note each time they receive a new one.

As for bitcoin, many people already keep their bitcoin in at regulated services like Coinbase that require customer ID. One day it may only be possible to send bitcoins from one regulated service to another, in which case a big chunk of the Bitcoin network will have become a closed account system, not an open one.

Why does all this matter?

Specialists need to be able to have conversations about their subject matter. Categorization is one of the ways to make these conversations flow without chaos. Are the categories we use for conversing on the topic of the economics of payments still sufficient? The world has changed. We've got new entrants like bitcoin and central bank digital currency. Garratt et al suggest that aging categories can "slow down progress in understanding intrinsic differences between the growing set of digital payment options and technologies."

But this case I think the old taxonomy are still useful, albeit with some tweaks.

P.S. Lawyers, regulators, users, and developers will all have different taxonomies for payments. Inter-taxonomic conversations are difficult, since a single term can mean something totally different. So stay within your taxonomy to avoid confusion.