Bringing back the Somali shilling

Somalia has long played host to one of the world's strangest monetary phenomenon, a paper currency without a central bank. I explored the idea of Somalia's "orphaned currency" more fully four years ago, but if you're in a rush what follows is the tl;dr version. Despite the fact that both the Central Bank of Somalia and the national government ceased to exist when a civil war broke out in 1991, Somali shilling banknotes continued to be used as money by Somalis. Over the years, Somalis also accepted a steady stream of counterfeits that circulated in concert with the old official currency, a state of affairs that William Luther explores in some detail here.

The story is worth revisiting because apparently Somalia's newly restored central bank is on the verge of re-entering the game of printing banknotes after a quarter century absence. With the help of the IMF, the Central Bank of Somalia (CBS) plans to issue new 1000 shilling banknotes, the introduction of higher denomination notes coming later down the road.

Old legitimate 1000 shilling notes and newer counterfeit 1000 notes are worth about 4 U.S. cents each. Both types of shillings are fungible—or, put differently, they are accepted interchangeably in trade, despite the fact that it is easy to tell fakes apart from genuine notes. This is an odd thing for non-Somalis to get our heads around since for most of us, an obvious counterfeit is pretty much worthless. The exchange rate between dollars and Somali shillings is a floating one that is determined by the cost of printing new fake 1000 notes. For instance, if a would-be counterfeiter can find a currency printer, say in Switzerland, that will produce a decent knock off and ship it to Somalia for 2.5 U.S. cents each (which includes the cost of paper and ink), then notes will flood into Somalia until their purchasing power falls from 4 to 2.5 U.S. cents... at which point counterfeiting is no longer profitable and the price level stabilizes.

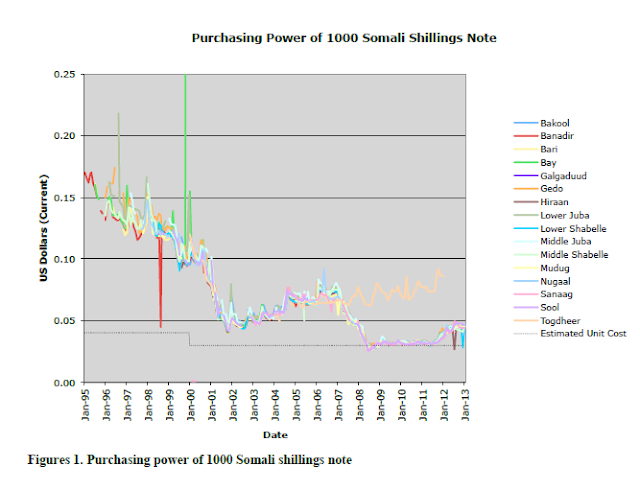

Below is the long-term price of Somali shillings, which I've snipped from Luther's paper. You can see how the purchasing power of a 1000 shilling note has fallen to what Luther calculates to be the cost of producing a new banknote, around 4 cents. His chart goes up to 2013, but if you look at the IMF's most recent report on Somalia (see Figure 3) you'll see that the exchange rate hasn't moved much.

|

| From Luther |

So with a new official banknotes on the way, what will happen to the old legacy notes and counterfeits? According to the IMF mission chief Mohammed Elhage, the IMF is in the midst of trying to determine at what price it will convert old notes for new official ones. So rather than repudiating counterfeits, the normal route taken by central bankers, the CBS will buy them up and cancel them. It will have to offer a decent price too, say like 5 or 6 U.S. cents for each 1000 note. If it makes a stink bid, say 3 U.S. cents, Somalis may simply ignore the appeal to bring in their old currency and keep using the old stuff. Because the buyback decision validates the work of counterfeiters, it just seems wrong. However, keep in mind that for the last twenty-five years it has been counterfeiters who have been willing to take on the risk of providing Somalis with a very real service, the provision of a working paper medium of exchange.

There is another good reason for buying up old legacy notes and counterfeits and cancelling them. If the CBS lets the old notes stay in circulation, then Somalia's ragtag multi-currency system will only get more confusing, with old legacy and counterfeit notes circulating concurrently with new shillings and U.S. dollars. With the new issue of shillings having a different purchasing power than the old ones, yet another floating exchange rate will be added to the mix. Who needs that sort of confusion? Better for the CBS to absorb the cost of buying up fakes in order to promote a more homogeneous currency.

***

As I pointed out in my old post, there's an old and nagging question in monetary economics that has never been satisfactorily answered: why is fiat money valuable? Somalia serves as a great laboratory to investigate this question because its situation is so unique. One famous answer to the riddle of fiat money is that governments use force to ensure that fiat money is valued. But this can't be the case in Somalia: it hasn't had a government since 1991, yet shillings continue to be accepted.

A second answer is that once money is valued—say because it a central bank has been pegged to an existing store of value like gold—then once the central bank disappears and the anchor is lost, those orphaned notes will continue to have value by dint of pure inertia and custom. This theory certainly seems to fit Somalia's experience.

The last theory is that when a central bank is destroyed, the money it issues will quickly become worthless... unless citizens expect a future central bank to emerge and reclaim the orphaned currency as its own. If so, it makes sense to keep using the currency since it isn't actually orphaned—it's on the way to being adopted. If the expectation is that this future central bank will also adopt counterfeit notes, it makes sense for people to accept all knock-offs as well. So we can tell a story that shillings, both real and fake, never fell to zero because enough Somalis had a hunch that a future body would reclaim them, a hunch that is on the verge of being realized as a newly-christened CBS seems set to buy old and fake shillings back. Were Somalis really this good at predicting the future? I don't know, but like the second theory, the last one seems to explain the data.

***

Personally, I think introducing a new paper currency is a bad idea. For some time now Somalia has been partially dollarized economy. U.S. dollar banknotes are the most popular paper currency, with old shillings being used in small payments and in the countryside. Mobile payments are extremely popular, but they are usually denominated in U.S. dollars, not shillings, and tend to be prevalent in cities where network coverage is best.

There are several problems with dual-currency systems like Somalia's. First, they impose a small but steady stream of currency conversion costs on the population, both the actual cost of shifting one's wealth from one to the other as well as the mental gymnastics involved in converting prices in one's head. Secondly, there are fairness issues. Civil servants are usually paid in the domestic currency and those in rural parts deal in the stuff. Urban private sector workers tend to earn dollars. In developing nations, dollars are usually more stable than domestic currency. As a result prices of houses, cars, and rent are often set in dollars. The class of folks who are paid in dollars make out better than the class that is earning shillings. Dollar earners never have to leave the much stabler dollar loop while those earning domestic currency suffer from constant slippage due to conversion costs and chronic inflation.

Now the IMF might argue that new shillings will completely expel dollars, thus forcing everyone into the same shilling loop and removing any monetary inequalities. But that's hog wash. The literature on dollarization teaches us that once the dollar begins to be used by a country—usually because the domestic currency has suffered from high inflation—it is very hard to remove it. Long after the local currency has been successfully stabilized, dollarization continues, an effect referred to by economists as hysteresis. Bring back the shilling and the dollar will stick around.

While bringing back new shillings doesn't make much sense, some sort of currency reform is probably worthwhile. While cities seem to be already well-served by dollars and mobile money, the rural population still relies on old and deteriorating shilling notes. Instead of foisting new shillings on these people, why not replace them with locally-minted small denomination dollar coins? I call this the Panama solution. For those who don't know, Panama is a dollarized nation. Due to the high costs of shipping in coins form the U.S., Panama mints its own dollar-denominated small change, paper money printed by the Federal Reserve taking care of the rest of the nation's physical money requirements.

By adopting the Panama model all Somalis would get to deal in U.S. dollars, thus removing any monetary class divisions. Gone too would be the headache of constantly converting between shillings and dollars, since with U.S. coinage there would only be dollars. And poor Somalians living in rural areas without phone coverage would finally get clean and homogenous small denomination cash.

Admittedly, there's far less for a central banker to do if he/she issues a narrow range of small denomination U.S. denominated coins, say 1¢, 5¢, and 25¢, rather than a full range of banknotes. It's certainly not sexy. But it would be cost effective. Coins, after all, last much longer than notes. This durability means that coins are a cheaper circulating medium for a central bank to maintain than paper. There is also the national ego that must be satisfied. What nation doesn't have its own currency? The worst reason to adopt a new shilling is because some concept of nationhood requires it—Panama has been using the dollar for decades, and this hasn't prevented it from becoming one of Central America's most successful nations.